Formats

Reporting on the child poverty related indicators#

New Zealand should be a place where all children and young people are loved, confident, happy and healthy, and are empowered to reach their full potential.

Too many children and young people live in families where it's a struggle to meet every day needs and do things that others take for granted. Nearly a quarter of New Zealand's children and young people (up to 240,000 children) are growing up in households considered to be in poverty,[a] when the cost of housing is taken into account.[1] For individual children, poverty is about growing up in a household that experiences financial hardship and the stress that arises from having to make decisions that involve trade-offs between basic needs. The experience of poverty can involve various forms of hardship, such as going hungry, living in cold, damp houses and foregoing opportunities, like school outings and sports activities.

Evidence shows that the experience of poverty in childhood, especially when that experience is severe and/or persistent, can have negative lifelong impacts. Children may be more likely, on average, to experience poorer educational outcomes, poorer health, and have more difficulty finding work in adulthood. The harmful effects also impact on society as a whole.

Our Government has passed ground-breaking legislation to make sure that Governments now - and in the future - are held to account for decisions that have economic, fiscal and wellbeing impacts on children living in poverty.

The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 (the Act) will help to ensure an enduring focus on reducing child poverty, political accountability against published three and ten year targets and transparent reporting on the progress we are making.

The Act includes a requirement for the Government to also report annually on one or more ‘child poverty related indicators' (CPRIs). These are measures related to the broader causes and consequences of child poverty, and/or outcomes with a clear link to child poverty. Taken together, these indicators help tell a broader story about life for children living in poverty in New Zealand, now and in the future, beyond what we can understand from observing trends against the income and material hardship primary and supplementary measures of child poverty. Over time, they can also tell us more about the real world impact of the policies we've put in place to reduce child poverty and mitigate its consequences.

The Government has identified its Child Poverty Related Indicators:

- Housing affordability - as measured by the percentage of children and young people (ages 0‑17) living in households spending more than 30 percent of their disposable income on housing.

- Housing quality - as measured by the percentage of children and young people (ages 0‑17) living in households with a major problem with dampness or mould.

- Food insecurity - as measured by the percentage of children (ages 0-15) living in households reporting food runs out often or sometimes.

- Regular school attendance - as measured by the percentage of children and young people (ages 6-16) who are regularly attending school.

- Potentially avoidable hospitalisations - as measured by the rate of children (ages 0-15) hospitalised for potentially avoidable illnesses.

Where data is available, we have included reporting on these indicators by ethnicity and household income or socioeconomic status. Please refer to the methodology section for more information on the different measures of income or socioeconomic status.

While the CPRIs are required under the Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018, they serve a dual purpose as indicators for three of the six outcome areas identified in the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy, required under the Children's Act 2014. The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy indicators tell a broader story about the state of child and youth wellbeing in New Zealand. You can find reporting information on the Child and Youth Wellbeing indicators at https://childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/measuring-success/indicators

The Act requires the Minister for Child Poverty Reduction to first report on the CPRIs for the 2020/21 financial year, after the Government Statistician has reported on the child poverty rates for that financial year (likely in early 2022). This current report is therefore intended to be a preliminary report and serve as a template for future reporting. For the food insecurity indicator in particular, we do not have data for the most recently completed financial year, so have included data for the last year the food insecurity module was included in the New Zealand Health Survey. Updated data on food insecurity will be available for next year's report, and this data will be gathered through the Health Survey every year going forward. The table below sets out details of data sources and reporting timeframes for each indicator.

| CPRI | Data source | Data lag | Frequency of reporting |

Next data available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing affordability | Household Economic Survey 2018/19 (Stats NZ) | Data based on annual household incomes data and experiences for households interviewed from mid-2018 to mid-2019, for the period 12 months prior (in some cases, back to mid-2017). | Annually | 2019/20 data available early 2021 |

| Housing quality | ||||

| Food insecurity | NZ Health Survey 2015/16 (Ministry of Health) | Data based on experiences for households interviewed from mid-2015 to mid-2016, for the period 12 months prior (in some cases, back to mid-2014). | Annually from 2019/20 | 2019/20 data available early 2021 |

| Regular school attendance | Attendance Survey 2019 (Ministry of Education) | Data based on attendance monitored over the course of Term 2 2019. | Annually | 2020 data available early 2021 |

| Potentially avoidable hospitalisations | Ministry of Health data 2018/19 | Data sourced from the National Minimum Dataset for Hospital Inpatient Events. Data required to be loaded within 21 days after the month of discharge. | Annually | 2019/20 data available early 2021 |

The publication of this report also comes at a time of significant and far-reaching challenge for New Zealand as a result of COVID-19. These challenges will impact every part of our economy and the livelihoods of many New Zealanders, including those on the lowest incomes. While it is still too early to know what the precise impact of COVID-19 will be on our economy, and on measured rates of child poverty, past experience and initial modelling by the Treasury indicate that rates of child poverty are expected to increase even in the short term.

This report focuses on trends up to and including the 2018/19 year. The data presented in this report was collected before COVID-19, and therefore serves as a pre-COVID baseline for many of the indicators. As a result of COVID-19, the trends that we were beginning to see for these indicators will likely shift, and for some indicators this shift could be significant. Our report in 2021 will also present pre-COVID data for a number of the indicators,[b] and we therefore won't be able to assess the full impact of COVID-19 on all of the CPRIs until our reports in 2022 and 2023.

Notes

- [a] The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 specifies ten distinct measures of child poverty, including measures related to income and material hardship. The measure referred to here is the low income, after housing costs - fixed-line measure (AHC50). Given the complexity of the issue it is important that all ten measures are considered together - no single measure tells us the complete story of child poverty on its own.

- [b] The Household Economic Survey (housing affordability and quality indicators) and New Zealand Health Survey (food insecurity indicator) were suspended at the end of March 2020, and therefore the 2019/20 data which we will report on next year is likely to be impacted for the COVID-19 lockdown period. Some data for the Term 2 school attendance survey will be collected for 2020, and therefore we will be able to show an immediate post-COVID picture in our 2021 report. Data for the potentially avoidable hospitalisations indicator is based on data collected by the Ministry of Health. This data has been gathered during the COVID-19 period, and will continue to be gathered until the end of the 2019/20 year. This means we will also be able to include a COVID-19 analysis for this indicator in our 2021 report.

Reference

- [1] Stats NZ. Child poverty statistics year ended June 2019. Wellington: Stats NZ. 2020. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/child-poverty-statistics-year-ended-june-2019

Housing affordability (ages 0-17) #

Housing affordability is a significant issue affecting many New Zealand families. Unaffordable housing often leaves families with insufficient money left to cover other basic household needs such as adequate nutrition, heating, clothing, and transport costs.[2] The additional financial stress and burden of unaffordable housing on parents can negatively impact on parental relationships, and parental mental health and health behaviours, which can in turn influence children's health and developmental outcomes.[3]

Attempts to economise can bring different risks to child wellbeing; for example, living in a house that is too small, poor quality, in an unsuitable location, or overcrowded. Living in a crowded house greatly increases the risk of transmission and experience of communicable diseases and respiratory infections.[4] It can also mean severely reduced personal space and privacy, inadequate space for children to do homework or study, and increases the chances of relational stress.[5]

Housing affordability can be measured in a number of ways. Spending more than 30% of disposable household income on housing costs for people on low incomes is conventionally considered unaffordable. In line with this, the CPRI for housing affordability is the proportion of children (ages 0-17) living in households spending more than 30% of their disposable income on housing costs. It is calculated using a ratio of gross housing costs (rates, dwelling insurance, mortgage and rent) to household disposable income (which takes into account taxes and transfer payments). The ratio is referred to as OTI (outgoings-to-income ratio).

What are the rates and trends for this child poverty related indicator?#

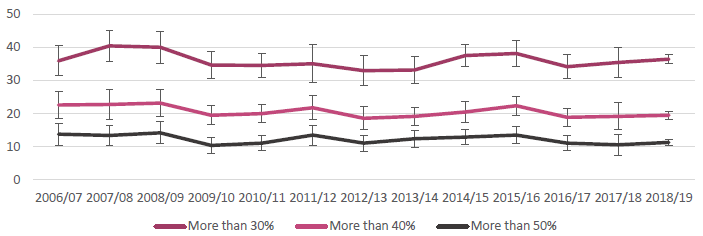

In 2018/19, 37% of children and young people (ages 0-17) lived in households spending more than 30% of their disposable income on housing. Taking the sample error into account, this is broadly aligned with the average over the period 2007-2019. For some households, housing stress is more severe, requiring families to spend more than 40% and 50% of disposable income on housing. In 2018/19, 20% of children and young people lived in households spending more than 40% of disposable income on housing; while 11% lived in households spending more than 50%.

Figure 1: Proportion of children living in households with OTIs of more than 30%, 40% and 50% (2006/07-2018/19)

Source: Household Economic Survey 2018/19, Stats NZ

It is important to understand recent changes within the context of longer-run trends for housing affordability, which are provided in the Ministry of Social Development's Household Incomes Report. This shows that the proportion of all under 65 households (not only those with children) with OTIs greater than 30% increased from around one in seven (14%) in the late 1980s to around one in three (35%) in the late 2000s, where it has broadly remained since. For households with the lowest incomes (quintile 1), the proportion with high OTIs continued to rise across the 2010s, irrespective of whether the benchmark was 30%, 40%, or 50%.

What are the rates for different socioeconomic groups? #

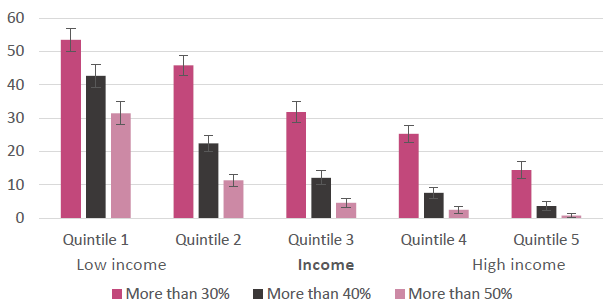

Low income households spend a greater proportion of their income on housing costs. Over half of children living in low income (quintile 1) households spent more than 30% of disposable income on housing costs, compared with 14% in quintile 5. Over 30% of children living in low income households spent more than 50% of disposable income on housing costs.

Figure 2: Proportion of children living in households with OTIs of more than 30%, 40% and 50% by annual household income quintile (2018/19)

Source: Household Economic Survey 2018/19, Stats NZ

What are other important observations from the data?#

There are significant differences in housing affordability across different types of housing tenure. In 2018/19, 42% of children living in dwellings not owned by their parents/caregivers had OTIs of more than 30%, compared with 33% for children living in owner-occupied dwellings. This pattern is consistent when looking at children living in households spending more than 40% and 50% of disposable income on housing costs.

There are likely to be particular groups who face worsening affordability outcomes that are not picked up by the measures. In particular, up until 2018 beneficiaries living in private rental accommodation were likely to have faced rents that increased in real terms, while incomes remained broadly flat. The Government has provided significant increases in incomes to many families through the Families Package and the COVID-19 response, and has also indexed benefits to wage growth from 1 April 2020.

Importantly, the HES data does not capture people living in non-private dwellings (i.e. living in motels, boarding houses or camping grounds), who are likely to face the most significant challenges with their housing situation.

To improve housing affordability we have

- Increased the Accommodation Supplement as part of the Families Package. The first stocktake since the implementation of the Families Package showed people receiving the Accommodation Supplement got an average increase from $71 to $98 a week.

- Introduced the Urban Growth Agenda to remove barriers to the supply of land and infrastructure and make room for cities to grow up and out.

- Increased the supply of public housing by over 6,400 places over four years, to bring the total number of public housing places in New Zealand to 73,628 by June 2022.

- Increased funding for Housing Support Products to help an additional 2,250 people per year access new housing or sustain their existing accommodation.

- Expanded Housing First to a total of 2,700 places to improve the social and housing outcomes of chronically homeless people and their families and whānau.

- Invested to maintain transitional housing places at approximately 2,800, and increase supply in the short term.

- Introduced the KiwiBuild programme to increase the supply of affordable homes for New Zealanders, including for first home buyers.

- Reduced the deposit required for a First Home Grant and Loan to five percent, making it easier for first home buyers to get a deposit together.

- Enabled family and friends buying a home together to each receive their full First Home Grant amount.

- Made $400 million available to support more New Zealanders into home ownership by increasing support for progressive home ownership products, such as shared equity and rent-to-buy schemes.

- Invested in the Māori Housing Network to provide additional papakāinga (Māori collectively owned homes), housing repairs, and capability building programmes.

In response to COVID-19 we have

- Protected housing costs for renters by providing a six month freeze on residential rent increases and increased protection from tenancy terminations.

- Worked with the major retail banks on mortgage deferrals for homeowners.

- Committed to deliver 8,000 new public and transitional housing places so that more New Zealanders can have a place to call home that is warm, dry and safe.

- Increased funding for the Ministry of Social Development's rent arrears assistance product to allow more people to access support to meet their housing costs.

References

- [2] Dockery, A. et al. Housing and children's development and wellbeing: a scoping study. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. 2010.

- [3] Clair, A. Housing: An Under-Explored Influence on Children's Wellbeing and Becoming. Child Indicators Research 12: p. 609-626. 2019

- [4] Environmental Health Indicators New Zealand. Household crowding. Wellington: Massey University. 2018. Available online: https://www.ehinz.ac.nz/indicators/indoor-environment/household-crowding/

- [5] Stats NZ. Living in a crowded house: Exploring the ethnicity and wellbeing of people in crowded households. Wellington: Stats NZ. 2018. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/living-in-a-crowded-house-exploring-the-ethnicity-and-well-being-of-people-in-crowded-households

Housing quality (ages 0-17)#

Living in a safe, warm, dry home is essential to children's wellbeing. In addition to its impact on immediate wellbeing, living in low quality housing makes children more likely to experience poor health, including respiratory illnesses and infections.[6]

It is estimated that around 30,000 children are hospitalised every year from preventable, housing-related diseases like asthma, pneumonia and bronchiolitis, with hospitalisation rates peaking in winter.[7] Young children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of poor housing as they spend proportionally more time indoors. Children and infants are also more susceptible to indoor air pollutants, as their immune systems are still maturing.[8]

There is a strong relationship between poor quality housing and poverty. The majority of lower-income families are living in rental accommodation which offers less security and stability and is often of poorer quality.[9] A lack of income is a barrier to accessing quality housing, especially in the context of increasing house prices, high and increasing rental costs, and the lower quality of houses available for rent. Low quality housing can also lead to further pressure on the household budget, as extra costs are incurred to keep un-insulated, cold houses warm, and also to access medical care.[10]

The CPRI for housing quality is the percentage of children (ages 0-17) living in households with a major[c] problem with dampness or mould over the past 12 months.

What are the rates and trends for this child poverty related indicator?#

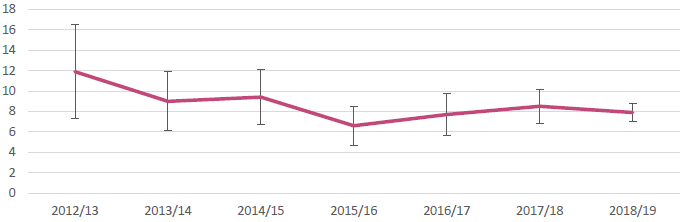

In 2018/19, 8% of children and young people (ages 0-17) lived in households reporting a major problem with dampness or mould. This is broadly the same as the proportion for 2017/18, and less than the average across the period 2013-2019 (9%).

Figure 3: Proportion of children living in households with a major problem with damp or mould (2012/13-2018/19)

Source: Household Economic Survey 2018/19, Stats NZ

While there is some evidence of a downward trend, it is still too early to know for sure, as sample errors on earlier HES were relatively high, and there were some slight reliability issues with HES data for 2015/16 and 2016/17.

What are the rates for different socioeconomic groups? #

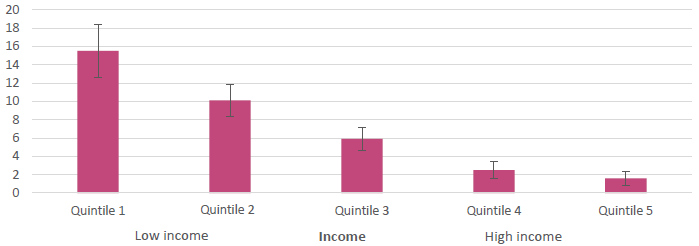

For children living in low income households, reported issues with damp and mould are more significant. For the year ended 30 June 2019, 16% of children aged 0-17 in quintile 1 (low income) lived in households reporting that damp and mould was a major problem. This compares to 2% of children aged 0-17 in quintile 5 (high income).

Figure 4: Proportion of children living in households with a major problem with damp or mould by annual household income quintile (2018/19)

Source: Household Economic Survey 2018/19, Stats NZ

What are the rates for different ethnic groups? #

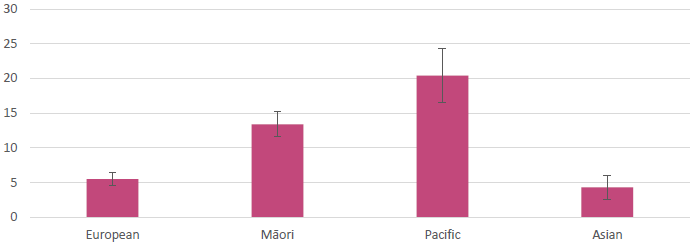

Housing quality issues are more pronouced for Māori and Pacific children. In 2018/19, 13% of Māori children and 20% of Pacific children lived in households with a major problem with damp or mould. This compares with 5% for European children, and 4% for Asian children.

Figure 5: Proportion of children living in households with a major problem with damp or mould by ethnicity (2018/19)

Source: Household Economic Survey 2018/19, Stats NZ

What are other important observations from the data?#

Housing quality issues are pronounced when looking at the data by tenure, with a significant proportion of children living in households not owning their own home reporting a major problem with dampness or mould (15% in 2018/19), compared with households living in owner-occupied dwellings (3%). This is broadly consistent with earlier Ministry of Social Development reporting on tenure, which also notes that 34% of those in state or social housing report such issues.[11]

To improve housing quality we have

- Improved the quality of housing and conditions for renters by implementing the Healthy Homes Guarantee Act 2017 and setting the Healthy Homes Standards. The Standards set minimum requirements for heating, insulation, ventilation, moisture and drainage, and draught stopping in residential rental properties, based on feedback from a wide range of public health experts and stakeholders including landlords, tenants and building experts. These changes are legislated for in the Residential Tenancies (Healthy Homes Standards) Regulations 2019.

- Introduced the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme that offers grants to cover two-thirds of the cost of ceiling and underfloor insulation. The programme also provides capped grants for heat pumps, wood burners and pellet burners. Government funded grants are topped up wherever possible by funding from community organisations. Homeowners with a Community Services or SuperGold Combo Card, families referred by the Ministry of Health's Healthy Homes Initiative, and those living in a lower-income area may qualify for a grant under this programme.

- Introduced the Winter Energy Payment, as part of the Families Package, to help those on a main benefit, receiving Superannuation or a Veteran's Pension with the cost of heating their homes over winter.

In response to COVID-19 we have

- Doubled the Winter Energy Payment and lengthened the payment period, to support beneficiaries and superannuitants to remain safe and well at home this winter. This payment gives beneficiaries and superannuitants $40.91 per week (for singles) and $63.64 per week (for couples or people with dependants).

- Expanded the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme and set aside funding to deliver subsidised insulation and heating retrofits in houses occupied by low income owners.

Note

- [c] Respondents to the HES are asked whether their house has a 'major' problem with damp or mould; a ‘minor' problem with damp or mould; or ‘no problem' with damp or mould.

References

- [6] Ingram T. et al. Damp mouldy housing and early childhood hospital admissions for acute respiratory infection: a case control study. Thorax 74: p. 849-857. 2019.

- [7] Child Poverty Action Group. A New Zealand where Children can flourish: Priorities for health. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. 2017. Available online: https://www.cpag.org.nz/campaigns/a-new-zealand-where-children-can-flourish/priorities-for-health/

- [8] Miller MD, et al. Differences between children and adults: implications for risk assessment at California EPA. International Journal of Toxicology 21(5): p. 403-418. 2002.

- [9] Johnson, A. et al. A Stocktake of New Zealand's Housing. Wellington: New Zealand Government. 2018.

- [10] Child Poverty Action Group. Our children, our choice: priorities for policy. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. 2014. Available online: https://www.cpag.org.nz/resources/our-children-our-choice-priorities-for-policy-7/

- [11] Perry, B. The material wellbeing of New Zealand households: trends and relativities using non-income measures, with international comparisons. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development. 2019

Food insecurity (ages 0-15)#

Food insecurity means not having reliable access to sufficient safe and nutritious food to lead a healthy and productive life, and meet cultural needs.[12] Both New Zealand and international research indicates a strong relationship between food insecurity and low income. When disposable income is limited, food is often one of the first items that is compromised.[13]

Food security is essential for children and young people to be happy and healthy, and learning and developing. Children living in food insecure households are less likely to consume nutritionally balanced diets essential for optimal growth and development, and this can have immediate and long term negative consequences for their health and education.[14] [15] Household food insecurity has been associated with a wide range of child health and development problems from infancy through to adolescence, including child obesity,[16] poor academic performance, and developmental and behavioural problems.[17]

Food insecurity contributes to family stress and can damage the nature of home environments when caregivers feel anxious about providing food, or are forced to rely on charity or emergency assistance programmes to feed their family. Although caregivers often shield children from the severity of the household's food insecurity by moderating their own food consumption, the increased stress on them and their families and whānau can also impact on parental mental health and parent-child relationships.[18] Family meals are also often central to spending quality time together, and in food insecure households this experience may be compromised.

The indicator for food insecurity is the percentage of children (ages 0-15) living in households reporting that food runs out often or sometimes, drawing on data from the New Zealand Health Survey's supplementary food security module. The last year this module was included in the Health Survey was 2015/16. The Health Survey includes the food security module in 2019/20, so we will be able to include updated data in our report on the CPRIs in 2021.

What are the rates and trends for this child poverty related indicator?#

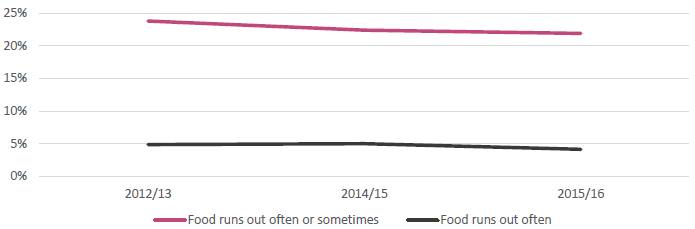

In 2015/16, 22% of children ages 0-15 lived in households reporting that food ran out often or sometimes. This was broadly the same as 2014/15, and down slightly from 24% in 2012/13. Of particular concern is the group reporting that food ran out often. In 2015/16 4% of children lived in households reporting that food ran out often, down slightly from 5% in 2014/15 and 2012/13.

Figure 6: Proportion of children living in households reporting food runs out often or sometimes, and often

Source: NZ Health Survey, Ministry of Health

What are the rates for different socioeconomic groups?#

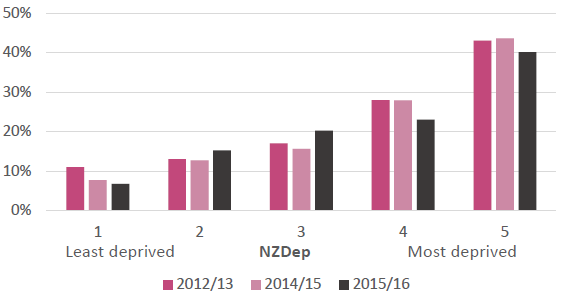

Food insecurity and geographic deprivation are also strongly correlated. In 2015/16, 40% of children in the most deprived areas (quintile 5) lived in households reporting food ran out often or sometimes. This compares with 7% of children in the least deprived areas (quintile 1). This rate is broadly the same looking at data from previous years. While some progress has been made in reducing food insecurity for children aged 0-15 overall, a gap remains between the experiences of children living in households in the most deprived and least deprived areas. This gap has not narrowed over time: in 2012/13 there was a 32 percentage point gap between children in households in quintile 5 and quintile 1 reporting that food ran out often or sometimes; widening slightly to 33 percentage points in 2015/16.

Figure 7: Proportion of children living in households reporting food runs out often or sometimes by NZDep quintile

Source: NZ Health Survey, Ministry of Health

What are the rates for different ethnic groups?#

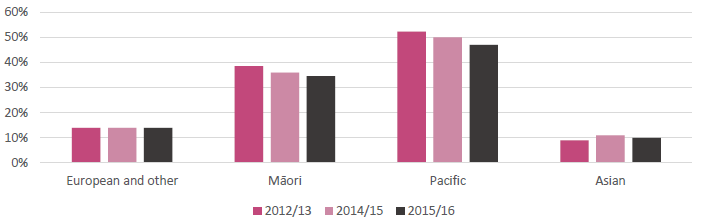

Food insecurity is disproportionately more prevalent amongst Māori and Pacific children and families. In 2015/16, 34% of Māori children and 47% of Pacific children lived in households reporting that food ran out often or sometimes. This compares with 14% for children identifying as European or other, and 10% for Asian children. Other analysis on food insecurity across ethnic groups has noted that, after adjusting for household income and size, the differences in food insecurity for different ethnic groups are no longer statistically significant, indicating thatother differences such as income and family structure are key factors.[19] [20] [21]

Figure 8: Proportion of children living in households reporting food runs out often or sometimes by ethnicity

Source: NZ Health Survey, Ministry of Health

What are other important observations from the data?#

While we do not have 2018/19 data on food insecurity from the Health Survey, we do have some indicators of demand for assistance with food from the Ministry of Social Development and NGOs. The Ministry of Social Development indicates a recent demand for hardship assistance, with money to buy food the main reason provided for needing hardship assistance. From October to December 2014-2019, 307,291 hardship assistance payments were provided for food.[22] However trends for hardship assistance are driven both by the level of underlying need and operational changes by MSD.

Recent analysis from the Salvation Army reported a small fall in the number of food parcels delivered by their network of foodbanks by 2.8% in December 2019 (around 1,700 parcels) from the year prior.[23] However, the Auckland City Mission reports that the demand for emergency food parcels is at an all-time high, with demand continually increasing over the past few years.[24]

It is clear that food insecurity is an issue for children in New Zealand, in particular for Māori and Pacific children living in areas of high deprivation. Forthcoming data from the New Zealand Health Survey for 2019/20 will paint a more up to date picture, and will be included in our CPRI report in 2021.

To improve food security we have

- Introduced a prototype programme to deliver free and healthy lunches in schools. The programme was introduced at the beginning of Term 1 2020 in 31 schools facing greater socioeconomic barriers in the Bay of Plenty/Waiariki and Hawke's Bay/Tairāwhiti, delivering lunch to around 7,000 students every day. Up to 21,000 students in around 120 schools will benefit from this pilot from the beginning of 2021. By providing healthy lunches, the programme aims to address barriers to school attendance and participation; support concentration, behaviour and achievement; boost overall student health and wellbeing; and reduce financial hardship facing families and whānau. The impact of the programme on these outcomes is being evaluated.

- Continued our funding support for the provision of food in schools through the KickStart Breakfast and KidsCan Food for Kids programmes.

In response to COVID-19 we have

- Expanded the free and healthy lunches in schools programme to up to 190,000 more Year 1-13 students in schools with the highest disadvantage.

- Scaled up existing programmes in schools and communities to provide an additional 10,000 fruit and vegetable boxes a week for 10 weeks.

- Provided additional support to foodbanks, food rescue and community food services.

References

- [12] Ministry of Health. Household Food Insecurity Among Children in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/household-food-insecurity-among-children-new-zealand-health-survey-jun19.pdf

- [13] Ibid.

- [14] Grant, C.C. et al. Nutrition and Indigenous health in New Zealand. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 46(9): p. 479-482. 2010.

- [15] Wynd, D. Hunger for learning. Nutritional barriers to children's learning. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. 2011.

- [16] World Health Organization. Double-duty actions. Policy brief. 2017.

- [17] Baer, T.E. et al. Food insecurity and the burden of health-related social problems in an urban youth population. Journal of Adolescent Health. 57(6): p. 601-607. 2015.

- [18] Ministry of Health. Household Food Insecurity Among Children in New Zealand.

- [19] Ibid.

- [20] Carter K, et al. What are the determinants of food insecurity in New Zealand and does this differ for males and females? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 34(6): p. 602-608. 2010.

- [21] Utter J, et al. Rising food security concerns among New Zealand adolescents and association with health and wellbeing. Kotuitui. 13(1): p. 29-38. 2018.

- [22] The Ministry of Social Development. Hardship Assistance - December 2019 quarter. Wellington: MSD. 2019. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/benefit/latest-quarterly-results/hardship-assistance.html

- [23] The Salvation Army. State of the Nation Report. Wellington: The Salvation Army. 2020. Available online: https://www.salvationarmy.org.nz/research-policy/social-policy-parliamentary-unit/latest-report

- [24] Auckland City Mission. Shining the light on food insecurity in Aotearoa. Auckland: Auckland City Mission. 2019. Available online: https://www.aucklandcitymission.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/org07307-ACM-world-food-day-A5_web.pdf

Regular school attendance (ages 6-16)#

Regular school attendance is important for student attainment and wellbeing, both in the short and long term. Sustained absence affects educational achievement and can lead to significantly diminished opportunities later in life. A New Zealand study found a strong relationship between student attendance during Year 10 and achievement in senior secondary school, with each additional absence predicting a consistent reduction in the number of NCEA credits a student subsequently attains.[25]

It is also likely that attendance impacts and is impacted by other aspects of subjective wellbeing, with research showing links between skipping school and schoolwork-related anxiety, bullying, a diminished sense of belonging, and lower levels of motivation. In every case, students who report skipping no days of school reported the best wellbeing outcomes.[26]

For some children in New Zealand, poverty and disadvantage can pose a barrier to regular school attendance. Some children and young people may be required to stay at home to look after younger siblings while parents and caregivers work, or work themselves to supplement family incomes. Others face particular challenges to maintaining regular attendance due to insecure housing and transience, and illnesses associated with disadvantage (including poor housing quality, overcrowding, and lack of access to primary health services). Lack of money to pay for school uniforms, PE gear, lunches, or travel to school can also make regular attendance a challenge.[27] [28]

The child poverty related indicator for regular attendance is the percentage of children and young people (ages 6-16) who are regularly attending school, based on the School Attendance survey. Students are classified as regularly attending school if they have attended more than 90% of Term 2, where time is measured in half-days. Students are otherwise classified into ‘irregular' attendance (attending 81-90% of the time), and ‘moderate' attendance (71-80% of the time) brackets. Students who have attended 70% or less of the time are classified as chronically absent. Absences can be classified as either justified (e.g. illness), or unjustified (e.g. truancy).

What are the rates and trends for this child poverty related indicator?#

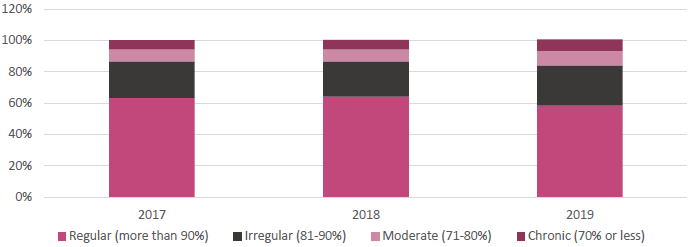

In 2019 59% of students (ages 6-16) attended school regularly. This was down from 64% in 2018, and 63% in 2017.

Figure 9: Proportion of students attending school by attendance category (2017-2019)

Source: Attendance Survey 2019, Ministry of Education[d]

When looking at the Ministry of Education's reporting on attendance of all students, a persistent trend of declining regular attendance can be observed from 2015 onwards, with more students falling into the irregular attendance bracket. Small increases can also be observed in the moderate attendance and chronic absence brackets.

What are the rates for different socioeconomic groups?#

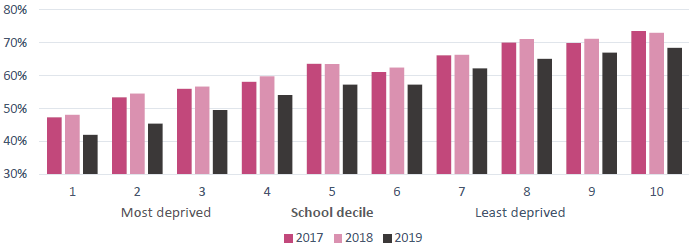

Regular attendance has a strong socioeconomic gradient, with lower regular attendance more pronounced in lower decile schools. In 2019, there was a 26 percentage point difference in regular attendance between students aged 6-16 in decile 1 and decile 10 schools. While the declining pattern of regular attendance is relatively consistent across students in different school deciles, the decreases are larger in lower decile schools.

Figure 10: Percentage of students attending school regularly by decile (2017-2019)

Source: Attendance Survey 2019, Ministry of Education

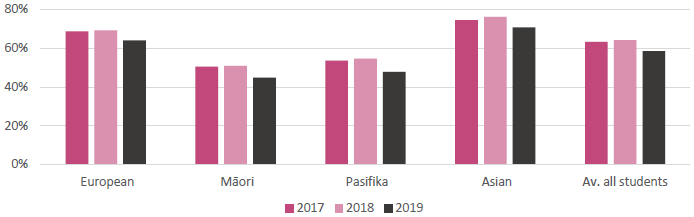

What are the rates for different ethnic groups?#

The declining pattern of regular attendance is also relatively consistent within each ethnic group. Māori and Pacific children have lower than average regular attendance. In 2019 45% of Māori children and 48% of Pacific children aged 6-16 attended school regularly (compared with an average across all students of 59%). This pattern is also consistent when looking back at attendance in 2017 and 2018.

Figure 11: Percentage of students attending school regularly by ethnicity (2017-2019)

Source: Attendance Survey 2019, Ministry of Education

What are other important observations from the data?#

The usual pattern for regular attendance by age is for attendance to peak at around the ages 9‑11, before dropping off as students get older. When looking at trends over time, the biggest change in regular attendance in 2019 can be seen in the decrease amongst primary aged children. The reasons for this decline are difficult to determine conclusively.

Figure 12: Percentage of students attending school regularly by age (2017-2019)

Source: Attendance Survey 2019, Ministry of Education

Text description of Figure 12: Percentage of students attending school regularly by age (2017-2019).

The Ministry of Education collects data on reasons for non-attendance, including justified and unjustified absences. Both categories have seen an increase, but the increase in justified absences were more substantial (1.0 percentage point from 2018, compared with 0.3 percentage points). An increase from 2018 in time off school due to illness (justified absence) was slightly heightened across primary school aged students, which partially accounts for the decline in regular attendance for younger children. These absences do not correlate with reported health data however. Cases of influenza were at about average levels across Term 2 in 2019. The number of measles cases peaked after the end of Term 2 and therefore is unlikely to be the cause of lower attendance in 2019.[29]

One factor strongly associated with low student attendance is children's experience of bullying. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) found that New Zealand children and young people are feeling increasingly unsafe at school and experiencing higher levels of bullying than they have in the past. The 2018 PISA results, published in late 2019, found that 15% of 15 year olds report being frequently bullied - double the OECD average.[30] These results are consistent with PISA 2015 (18% of 15 year olds reported being frequently bullied, compared with an OECD average of 9%).[31]

Overall, there are many drivers that influence school attendance rates, and no one driver stands out as a reason for declining regular attendance on its own. The Ministry of Education will continue to monitor trends in school attendance, and consider potential responses to the data.

To improve regular attendance we have

- Introduced two pilots in South Auckland and Kawarau to pilot a new design of the Attendance Service, with a view to changing the nationwide service offering over the medium-term.

- Initiated a review of the codes used to record a student's presence or absence, as well as collecting attendance data across the year to gain richer insights into the reasons for non-attendance. We are also reviewing our guidance to schools around managing attendance.

- Initiated an innovation project focusing on attendance, funded through the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) Digital Government Partnership Innovation Fund. This project will trial interventions to make a difference in improving attendance and to help lift the Ministry's innovative capacity and capability. The Ministry is working with The Southern Initiative/Auckland Co-Lab and the Innovation Unit to explore insights, ideas and prototypes that could support a response to this challenge in Manurewa and the Bay of Plenty.

- Worked closely with schools and with other agencies (e.g. Oranga Tamariki, the Ministry of Social Development and Police) to improve attendance and engagement, and sharing good practice with schools, including:

- brokering services for learners and whānau

- providing support for student pathways to help students transition out of school and into work or further education

- developing joint work/action plans to ensure actions are co-ordinated across agencies

- working with schools and the sector to develop strategies for addressing poor attendance

- working with and monitoring attendance service providers

- new initiatives and pilots, e.g. mentoring programmes.

- This work is complemented by action across the wider Education Work Programme that is anticipated to contribute to reversing inequities in learning, engagement and attendance. These include a significant strengthening of Learning Support, school leadership with a sustained focus on quality teaching practice, a localised curriculum and pastoral care.

- Engaged in a social media campaign to encourage parents to ensure their children are at school every day they are well enough to be there, reaching 100,475 people across Twitter and Facebook between February and March 2020.

In response to COVID-19 we have

- Provided emergency funding for television content and hard copy learning packs to supplement distance learning for early childhood education and schooling, to maintain engagement while schools were closed during the COVID-19 containment period.

- Provided funding for devices and connectivity to enable student access to online teaching and learning.

- Provided advice, guidance and support for early learning services, schools and kura through each alert level and in preparation to open.

- Responded to parental and caregiver anxiety preventing attendance with information providing assurance that schools are safe to attend and have measures in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

- Implemented a national plan for working collectively with schools on new attendance and engagement approaches to support all children and young people to return to early learning, school and kura following the COVID-19 containment period.

- Worked across agencies to support the identification of absentee/non engaged families and welfare checks.

- Topped up the School High Health Needs Fund that provides teachers' aide support for students with high health needs so they can attend school safely.

Notes

- [d] This graph displays the proportion of students aged 6-16 attending school regularly. The rates for the irregular, moderate and chronic attendance categories are based on all students in Years 1-13. The rates and trends observed across all students are broadly the same for students aged 6-16 only.

References

- [25] Webber, A. He Whakaaro: What is the relationship between attendance and attainment? Wellington: Ministry of Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/he-whakaaro/he-whakaaro-what-is-the-relationship-between-attendance-and-attainment

- [26] McGregor A. and Webber A. He Whakaaro: School attendance and student wellbeing. Wellington: Ministry of Education. 2020. Available online:https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/he-whakaaro/he-whakaaro-school-attendance-and-student-wellbeing

- [27] Ministry of Education. Children living in low income households. Wellington: Ministry of Education. 2012. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/indicators/definition/family-and-community-engagement/children_living_in_low_income_households

- [28] White, M. et al. Poverty and education: A teacher's perspective - Summary of the findings of the focus group research. British Columbia: British Columbia Teachers' Federation. 2012. Available online: https://www.bctf.ca/PovertyResearch.aspx

- [29] Ministry of Education. New Zealand School Attendance Survey: Term 2, 2019. Wellington: Ministry of Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2503/new-zealand-schools-attendance-survey-term-2,-2019

- [30] Ministry of Education. 2018 PISA survey findings published. Wellington: Ministry of Education. 2019. Available online: http://www.education.govt.nz/news/2018-pisa-survey-findings-published/

- [31] OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students' Wellbeing. Paris: OECD. 2017.

Potentially avoidable hospitalisations (ages 0-15)#

Every year thousands of children across New Zealand are admitted to hospital with avoidable illnesses and injuries.[32] Potentially avoidable hospitalisations (PAH) include illnesses and injuries that can be pre-empted through more effective primary health care services, or broader public health and social policy interventions that target the underlying determinants of health.

Exposure to tobacco smoke, poor housing conditions, inadequate or poor nutrition and oral hygiene, and failure to vaccinate are just some of the drivers of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for children. Potentially avoidable hospitalisations include respiratory conditions, gastroenteritis, skin infections, tooth decay, vaccine preventable illnesses, and physical injuries. Health issues in childhood can have an impact on longer term health outcomes. Many adult health problems have roots in childhood experiences, such as chronic lung disease among adults, cardiovascular disease, mental illness, dental decay and shortened life expectancy.[33]

For some children in New Zealand, low income can be a barrier to accessing primary health care in order to treat illnesses and receive vaccinations.[34] This can include the cost and time of travelling to a health centre, or parents taking time away from work to attend appointments with their children. Low income also acts as a barrier to accessing better quality housing and a healthy diet, both of which are strongly related to poor health outcomes.[35]

This indicator looks at the rate of children ages 0-15[e] hospitalised for potentially avoidable illnesses and injuries, based on data collected by the Ministry of Health. Data for this indicator includes hospitalisation as a result of intentional and unintentional injuries, which are part of the Ministry of Health's official definition of potentially avoidable hospitalisations.

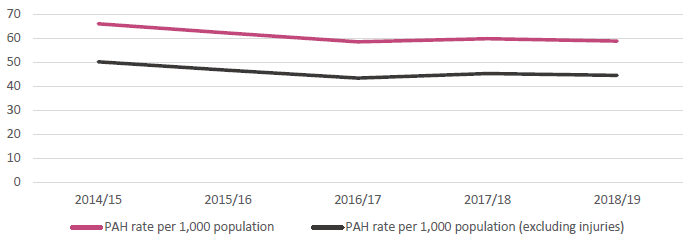

What are the rates and trends for this child poverty related indicator?#

In 2018/19, the rate of potentially avoidable hospitalisations was 59 per 1,000 children (ages 0-15). Age standardised rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations have been going down in New Zealand over the four years to 2018/19, from 66 potentially avoidable hospitalisations per 1,000 children aged 0-15 in 2014/15. This trend is the same when looking at rates for illnesses only (excluding injuries), where rates per 1,000 children aged 0-15 decreased from 50 in 2014/15 to 45 in 2018/19.

Figure 13: Age standardised PAH rate per 1,000 children aged 0-15 (2014/15 - 2018/19)

Source: Health and Disability Intelligence, Ministry of Health

What are the rates for different socioeconomic groups?#

Rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations are more pronounced among children living in more deprived areas. In the most deprived areas (quintile 5) in 2018/19, the rate of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for children aged 0-15 was 80 per 1,000; compared with 44 per 1,000 children living in the least deprived areas (quintile 1). Rates for quintile 5 (and other more deprived quintiles) declined rapidly over 2014/15 - 2016/17, but have remained broadly flat in more recent years. This steep decline is mirrored in the ethnicity data.

Figure 14: Standardised PAH rate per 1,000 children aged 0-15 by deprivation quintiles (2014/15 - 2018/19)

Source: Health and Disability Intelligence, Ministry of Health

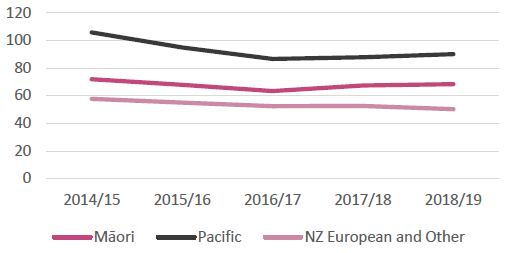

What are the rates for different ethnic groups?#

Māori and Pacific children are over-represented in rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations, and while reducing rates can be observed until 2016/17, progress on these rates has levelled off in recent years. In 2018/19, potentially avoidable hospitalisations for Pacific children aged 0-15 were 90 per 1,000 children; and 68 per 1,000 children for Māori children. This compares with 50 per 1,000 children for European and other. These findings are similar to those of a Canterbury University study, which found that rates for all illnesses, particularly respiratory illnesses, are highest among Māori and Pacific children.[36]

Figure 15: Age standardised PAH rate per 1,000 children age 0-15 by ethnicity (2014/15 - 2018/19)

Source: Health and Disability Intelligence, Ministry of Health

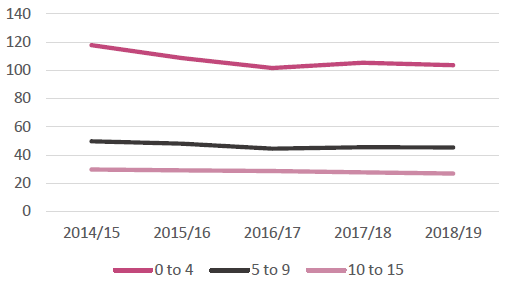

What are other important observations from the data?#

Age specific rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations are highest amongst younger children. In 2018/19 the rate of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for children aged 0-4 was 104 per 1,000 children, compared with 27 per 1,000 children aged 10-15. Younger children are particularly vulnerable to unhealthy environments (e.g. low quality housing) due to their still-developing immune systems. Recent research by the University of Canterbury indicates that up to a third of all hospitalisations for children under five could be avoided with good access to quality housing, health services and fluoridated drinking water.[37]

Figure 16: PAH rate per 1,000 children by age group (2014/15 - 2018/19)

Source: Health and Disability Intelligence, Ministry of Health

Text description of Figure 16: PAH rate per 1,000 children by age group (2014/15 - 2018/19).

Age standardised rates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations were highest for respiratory conditions (17 per 1,000 children in 2018/19), followed by unintentional injuries, including falls and burns (14 per 1,000 children). Other notable conditions included gastrointestinal diseases (6 per 1,000 children) and dental conditions (5 per 1,000 children).

To improve potentially avoidable hospitalisations we have

- Extended free and low-cost doctors' visits for children under the age of 14 enrolled with a GP, reaching 56,000 more young people.

- Lowered the cost of visiting a doctor or nurse for adults with a Community Services Card, and their dependants aged 14 to 17 years, who are enrolled with a GP.

- Expanded and enhanced school-based health services to reach over 80,000 students in decile 1-5 schools.

In response to COVID-19 we have

- Continued to support the sustainability of WellChild Tamariki Ora service providers through Budget 2020 to deliver child health services including immunisations, health checks and other essential services.

- Boosted funding for Whānau Ora to support the health and wellbeing of whānau and communities.

Notes

- [e] The data reported here includes children aged 0-14.9999999 years and is reported as children aged 0-15.

References

- [32] Child Poverty Action Group. A New Zealand where Children can flourish: Priorities for health.

- [33] Ministry of Health. Health and Independence Report 2017: The Director General of Health's Annual Report on the State of Public Health. Wellington: Ministry of Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/corporate-publications/health-and-independence-reports

- [34] Bidwell, S. Improving access to primary health care for children and youth. Christchurch: Canterbury DHB. 2013. Available online: https://www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/accessprimarycarechildrenyouth.pdf

- [35] Braveman, P. et al. How does housing affect health? Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2011. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/05/housing-and-health.html

- [36] Hobbs. M, et al. Investigating the rates and spatial distribution of childhood ambulatory sensitive hospitalisations in New Zealand. Christchurch: University of Canterbury. 2019. Available online: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/16898

- [37] Ibid.

Annex 1#

Further details on data, including sources and methods#

Approach to reporting on data by socioeconomic group

We have reported on each indicator by socioeconomic status. We have used different measures of socioeconomic status across the indicators:

- Annual household income quintiles (used for the housing affordability and quality indicators): Though it is recognised that socioeconomic disadvantage usually reflects a broader range of factors than income, household income is used as a proxy for socioeconomic status in this report. Income groups are quintiles (to the nearest hundred dollars) of household equivalised disposable income. Equivalised income is a measure of household income that takes account of the differences in a household's size and composition. Quintiles are formed by dividing the total population of households into 5 groups of equal size, based on their equivalised disposable income.

- NZDep quintiles (used for the food insecurity and potentially avoidable hospitalisations indicators): NZDep is an index of socioeconomic deprivation based on Census data relating to income, home ownership, employment, qualifications, family structure, housing, access to transport and communications. It provides a deprivation score for each meshblock (smallest geographical area) in New Zealand. This report uses NZDep quintiles, where quintile 1 represents the 20 percent of small areas with the lowest levels of deprivation (the least deprived areas) and quintile 5 represents the 20 percent of small areas with the highest level of deprivation (the most deprived areas).

- School deciles (used for the regular school attendance indicator): Deciles are a measure of the socioeconomic position of a school's student community relative to other schools throughout the country. A school's decile is based on the small Census areas where its students live (meshblocks), not on the general area of the school. Deciles are based on five equally weighted socioeconomic indicators for a community (including household income, parent occupation, household crowding, parent qualification and income support receipt). The Ministry of Education's school decile system is used to target funding to help schools overcome any barriers to learning that students from lower socioeconomic communities might face (the lower the school's decile, the more funding it receives).

Housing affordability and quality

The data on housing affordability and quality was prepared by Stats NZ based on the Household Economic Survey (HES). HES collects information on household income, savings, and expenditure, as well as demographic information on individuals and households. For HES 2018/19, changes to the survey including a larger sample size means the housing affordability and quality indicators can be reported on by income quintile and ethnicity (this has not been possible previously). In addition, to improve data precision, income data is based on administrative data from the IDI, rather than respondents being required to answer this question themselves. Further information on the HES methodological changes can be found on the Stats NZ website at https://www.stats.govt.nz/methods/changes-to-the-household-economic-survey-201819

For the housing affordability indicator, the OTI ratios are not mutually exclusive. Households that spend more than 40% of their household disposable income on housing costs will also be included in the more than 30% category.

The data for quintile 1 (lowest income quintile) includes loss from investments or self-employed income, or no income received. Investigation by Stats NZ of the characteristics of the households that make up the group with very low income has shown that many of these households do not have the high deprivation scores we might expect of households with low income. This suggests that either the reported income value is incorrect, these households have access to economic resources such as wealth, or that the instance of low or negative income is temporary. This has an impact on the data reported for quintile 1.

Food insecurity

The data on food insecurity is based on a single question asked as part of the New Zealand Health Survey. The question was last asked in 2015/16, and was asked as part of the 2019/20 survey (in the field until end March 2020). The question is one of eight that makes up the food security index, which is a weighted combination of responses to the following questions by the adult respondent, answering often, sometimes or never:

- We cannot afford to eat properly

- Food runs out in our household due to lack of money

- We eat less because of lack of money

- The variety of foods we are able to eat is limited by a lack of money

- We rely on others to provide food and/or money for food, for our household, when we don't have enough money

- We make use of special food grants or food banks when we do not have enough money for food

- I feel stressed because of not having enough money for food

- I feel stressed because I can't provide the food I want for social occasions

The answers to the questions are used as a basis to determine severe-to-moderate food insecurity, and severe food insecurity, among children in New Zealand households. A 2019 report on household food insecurity among children in New Zealand can be found on the Ministry of Health website at https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/household-food-insecurity-among-children-new-zealand-health-survey

The data used in this report do not impute values for responses where interviewees answered ‘don't know', or refused to answer the question. Therefore, the data reported here differ slightly from those reported by the Ministry of Health's food security publication, for which imputed responses were used.

Regular attendance

The Ministry of Education reports annually on student attendance, based on data generated during Term 2 of the school year (between the end of April and beginning of July). It is a voluntary survey run across primary and secondary schools. Regular attendance is defined as students attending school for more than 90% of available half days.

The Ministry of Education's attendance data does not report on student attendance by age. The Attendance Survey covers all students (aged 5 to 18+) from participating schools, and the data is presented by student year levels.

This CPRI specifically looks at the attendance rates of students ages 6 to 16, whereby age is determined by joining attendance data with the National Student Index. Through doing so, we note minor differences to the Ministry of Education's published results. These have an immaterial impact on overall results and trends (+/- 1%).

The Ministry of Education's report on 2019 attendance for all students can be found at https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2503/new-zealand-schools-attendance-survey-term-2,-2019

Potentially avoidable hospitalisations

The Ministry of Health does not routinely collect data on potentially avoidable hospitalisations. In order to present data for this indicator, the Ministry of Health used the National Minimum Dataset (Hospital Inpatient Events) and developed a specific methodology based on analysis from academic literature and discussions with experts. The methodology report has been published by the Ministry of Health (Ministry of Health. Indicator of potentially avoidable hospitalisations for the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy: A brief report on methodology. Wellington: Ministry of Health. 2020).